Waukeshahealthinsurance.com-

Waukeshahealthinsurance.com-

Cape May, New Jersey

–

First come the horseshoe crabs. They lift their spherical shells and leave Delaware Bay under the first full moon in May to mate and lay eggs.

The birds will soon follow. Hundreds of thousands of squawks and seabirds descend on these beaches to feast on the protein and fat-rich eggs. Within a week, some birds double in weight as they prepare to continue their journey between South America and their summer breeding grounds in the Arctic. Every spring, up to 25 different species of birds stop here.

It's an ecological wonder like no other in the world, and bodes well for scientists looking to stop the next outbreak.

This year, their work as a Dangerous flu virusH5N1, tear in dairy cattle and poultry herds in the United States. The world is watching to see if the threat worsens.

The work on this beach helps clarify this.

“It's a treasure in this area,” says Dr. Pamela McKenzie, referring to her research partner, Patrick Seiler.

McKenzie and Seiler are part of a National Institutes of Health-funded team coming to the beaches near St. Jude Children's Research Hospital. over here For 40 years to collect bird species.

The project is the brainchild of Dr. Robert Webster, a New Zealand virologist who first discovered that influenza viruses are found in the intestines of birds.

“We were most surprised. Webster, who is now retired at 92 and still joins the collection, was not in the trachea, but in the gut, and they were reproducing it in the water. Travel when you can.

The feces or guano of infected birds is becoming infected with viruses. Of all known influenza subtypes, Except for two Found in birds. The other two subtypes were found only in bats.

In the year Birds on the Atlantic Flyway, which runs between the Arctic Circle in South America and northern Canada.

Finding a new flu virus here could give the world an early warning of an upcoming pandemic.

The project has become one of the longest-running influenza sampling projects of the same bird species in the world, said Dr. Richard Webby, who led the Webster-initiated project. Webby directs research on the ecology of animal influenza at the World Health Organization Collaborating Center in St. Jude.

Predicting epidemics is like trying to predict hurricanes, Webby explains.

“In order to predict bad things, whether it's a hurricane, whether it's an epidemic, you have to understand the current norm,” Webby said. “Then we can see when things diverge, when they switch hosts, and what drives those transitions.”

The US is now in the midst of one of those transitions. A few months before the St. Jude team arrived in Cape May this year, H5N1 was first detected in dairy cattle in Texas.

The discovery that H5N1 can infect cows has put flu experts, including Webb, on alert. Influenza-type viruses such as H5N1 have never been transmitted in cows.

Scientists have followed H5N1 for more than two decades. Some influenza viruses show no or only mild symptoms when they infect birds. These are called viruses

Low Pathogenic Avian Influenza or LPAI. H5N1, which makes birds very sick, is called HPAI, for highly pathogenic avian influenza. It destroys flocks of farm birds such as chickens and turkeys. In the US, infected flocks are culled or culled as soon as the virus is detected to prevent the spread of the disease and alleviate the suffering of the birds.

It's not the first time US farmers have caught the highly pathogenic bird flu. In 2014, they brought migratory birds from Europe H5N8 viruses To North America. Violent evacuations that killed more than 50 million birds ended that epidemic, and the US has been free of highly pathogenic bird flu viruses for years.

However, the same strategy did not stop H5N1. H5N1 reached the US in late 2021, and continues to spread even as infected chicken flocks begin to decline dramatically. Over the past two years, H5N1 viruses have evolved the ability to infect a variety of mammals, such as cats, foxes, otters and sea lions, making them a step closer to easily spreading to humans.

H5N1 viruses can infect humans, but these infections are not yet transmitted from person to person because the receptors on cells in the nose, throat, and lungs are slightly different from the cells in the lungs of birds.

But it doesn't take much to change that. A A recent study In the journal Science, a key change in the virus's DNA allows it to implant itself in cells in the human lung.

The team at Cape May He never found H5N1 in the birds he sampled. But with the virus spreading among cows in several states, they wondered where else it could be. Did it happen to these birds?

McKenzie and Seiler hiked up Bogma Beach in boots, gloves and face masks last spring. They scoop fresh white guano out of the sand and hold dozens of washes in their pockets with plastic bottles held together between their fingers. As the bottles were brought down to the beach, they were returned to neatly stacked trays in the beige cooler that Sailor carried over his shoulder. In one week, the team collects 800 to 1,000 samples.

Any flu viruses in the samples will be sequenced – the exact letters of the viruses' genetic code are read – and uploaded to an international database, such as A reference library to help scientists track influenza strains as they travel the world.

The big white drops belong to seabirds — black-headed laughing gulls and white-headed herrings — McKenzie explained. The team plans to conduct a separate study this year focusing on seagulls.

“There are some viruses that we've only found in labor,” Seiler said.

Some of the white splats, lines with egg bumps still inside, are small birds called semipalmated sandpipers.

A few yards away, brown birds called dunlins, searching the sand for crab eggs with their long black beaks, watched in awe as Sailor and McKenzie made their way to the beach.

Some of the samples they were collecting were shipped on ice to Memphis, Tennessee; Where St. Jude is located, others travel across town to an RV park, where Dr. Lisa Kercher is waiting for them.

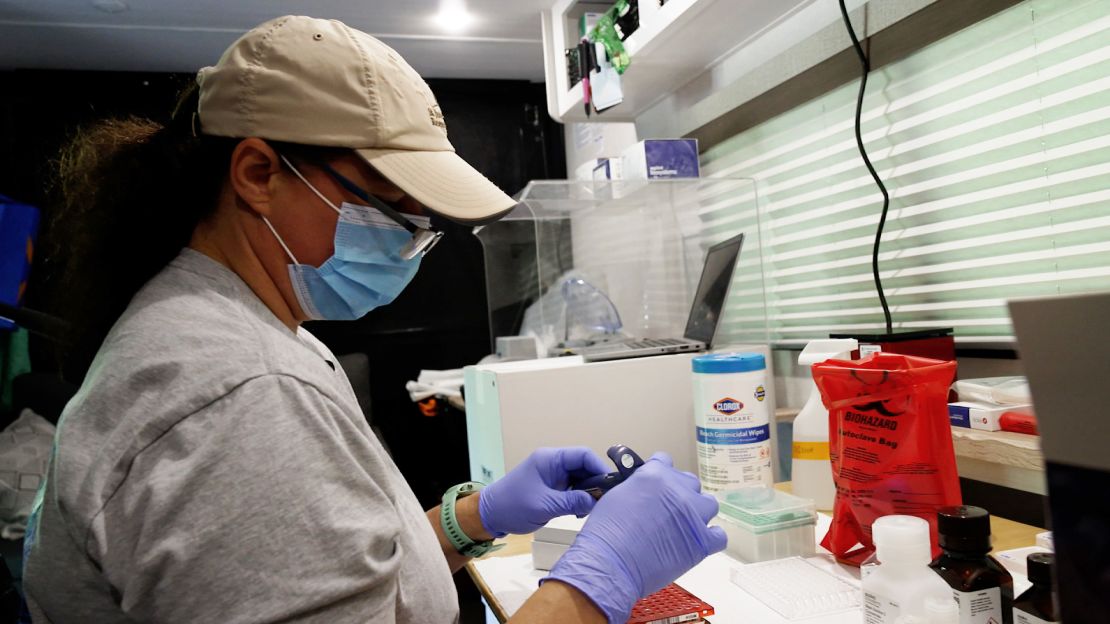

Kercher, director of lab operations at St. Jude, is standing among other campers, converting a typical RV into a mobile lab. This year, she was experimenting on the field to see if it would speed up the team's work.

“We take samples in the field and bring them back to the lab and then we have technicians working diligently on these thousands of samples,” Kercher said. It could be months before the team knows the exact strains of the virus they have found.

“For example, if I'm here in May, I don't know the subtype of these viruses until September or October,” she said.

Kercher's goal is to quickly screen samples in the field to see if they contain influenza viruses. About 10% of the samples that come in each year are positive for the flu virus. If she can send only positive samples to the lab, they can process them faster.

After following up the samples this year, they found no H5N1 in either the Cape May samples or the duck samples from Canada.

“We don't really know why,” Kercher said in an interview last week. “So we've always been a little curious.”

After finishing at Cape May, Kercher took his mobile laboratory to the Peace River in northern Alberta, Canada, to examine ducks breeding during the summer. The team has traveled to Canada to test ducks for 45 years, but this is the first year they've used the mobile lab there. After the Alberta trip, Kercher drove her RV to Tennessee to check on more ducks where they were roosting for the winter.

in the meantime, The virus was swirling around them, popping up in herd after herd of cows in the Midwest and then in California. Dozens of infections have been reported among farmers, but in Related to dairy cattle It was mostly mild. Human-to-human transmission has not been reported.

The cattle outbreaks seem to have cooled off briefly in late summer. Then came a serious human infection.

First, the teenager was hospitalized in Vancouver, Canada. Difficulty breathing. Then, more recently, A man in Louisiana He became seriously ill with H5N1 after being exposed to a backyard flock. In both cases, the virus is slightly different from that circulating in cows. The virus identified in cattle is of the B3.13 genotype, while the D1.1 genotype found in both severe human infections is circulating in wild birds and poultry. As he says US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Other D1.1 infections have been in humans, as well as, in Washington state, in poultry workers. Those cases were not that serious.

After losing the virus in the spring and summer, the St. Jude team moved its mobile lab to a place it had never tried before: a large wintering area for mallards and other ducks in northwest Tennessee.

534 fight ducks There, in November and December, and in about a dozen samples, the D1.1 genotype of the virus was found.

“We've got the same pressure that's causing all the havoc in humans and wild birds,” Kercher said.

D1.1 is a new group of viruses. Scientists do not know much about it As you know about cattle viruses. But they said the team's samples helped them link the virus to the Mississippi Flyway, which follows the Mississippi River through central Canada and into the Gulf of Mexico.

…