Waukeshahealthinsurance.com-

Waukeshahealthinsurance.com-

–

One day in September, I stood in front of my open refrigerator, full of anger but unable to figure out what to eat.

I was worried that whatever I chose to eat would cause the new app on my phone to increase my glucose levels by the number allowed for my day – and I was determined to beat this algorithm.

I just wore it. Continuous glucose control A device that uses a tiny needle to give you up-to-the-minute information on how well your blood sugar is moving—not that I have diabetes, but the main use for things called CGMs, but these devices are starting to be marketed to everyone as safety devices, and I wanted to see how they worked.

Apple? Too much sugar. A granola bar? Hello, glucose level. Cheese is the ticket. Within a few days of wearing this monitor, cheese taught me not to raise my glucose levels.

“Did this thing happen to you without knowing it?” keto diet? My husband – who had looked at a few hanging parts while I was trying to figure out how to make my CGM happy – finally asked.

so beautiful. Avoiding carbs and prioritizing protein and fat, often together, my CGM and app; Lingo From the health company Abbott, it counted on me.

But because I wasn't aiming to change to a very low-carb, ketogenic diet, I struggled to know what to eat first; In the first week or so of wearing the CGM, my scale read 3 pounds lower than usual – I think it's a fluke, because I'm too scared to eat a regular meal.

This is not surprising, experts say how CGMs should be used, whether you have diabetes or not.

Continuous glucose monitors are revolutionary for people with type 1 diabetes, for whom glucose levels are life and death, providing information on how much insulin they need to keep blood sugar levels stable. It is the alternative. Finger stick testA finger prick to draw drops of blood to measure glucose levels several times a day.

“CGMs are life-changing for insulin-dependent diabetics,” he said Laura MarstonA lawyer and advocate for low insulin prices, he was diagnosed with type 1 diabetes as a teenager. Before getting a CGM, she said she would go long periods of time without checking her glucose levels, instead adjusting her insulin doses based on her mood, leading to hospitalizations. Diabetic ketoacidosis.

Now, Marston knows her glucose level every five minutes with her CGM, and her other blood glucose measure, A1C, is consistently better — something she says she's paying attention to both the CGM and the issue. With diabetes and permanent health insurance.

In that context, CGMs are medical devices that require a prescription and: NormallyBut not always – getting health insurance coverage. CGMs may also be covered for people with type 2 diabetes who use insulin.

But this year Dexcom And AbbottThe two major CGM makers have introduced biosensors to people who don't use insulin, which are over-the-counter and $89 per month out-of-pocket.

It was a Dexcom offering called Stelo. It has been cleared According to data from the US Food and Drug Administration in March, the device performed similarly to other CGMs in a clinical study.

Dr. Jeff Shuren, director of the agency's Center for Devices and Radiological Health, said in a statement released by the FDA that “CGMs can be a powerful tool to help manage blood glucose” and that “giving more individuals important information about their health, whether it's access to a doctor or health insurance, will advance health equity for American patients.” It is an important step.

It was Abbott's lingo. It has been cleared in June and is specifically aimed at “consumers who want to better understand and improve their health and well-being,” the company said in a news release.

The idea is that looking at the immediate response to the glucose effects of food, exercise, sleep and stress can help them understand the specific ways their bodies respond to different inputs and make changes to improve their health.

I'm excited to try it. Putting the device on was surprisingly painless, and an hour after the little disc was placed on my arm, I started seeing my glucose levels on the app on my phone.

I sent a message saying “117”. Dr. Jody Dushaya physician at Beth Israel Deacon Medical Center who works with people with obesity and diabetes and offered to review my CGM findings with me.

The Lingo app tells me that 70 to 140 milligrams per deciliter is in the “normal, healthy glucose range,” adding, “Occasionally you may find yourself above 140 mg/dL or below 70 mg/dL, which is expected.”

Dushay warned me before placing the CGM that postprandial blood sugar in a generally healthy young woman can range from the 50s fasting to the 150s. She also emphasized that continuous glucose monitoring should not be used to diagnose prediabetes or diabetes.

Her warning on how to respond when my data is found to be compromised.

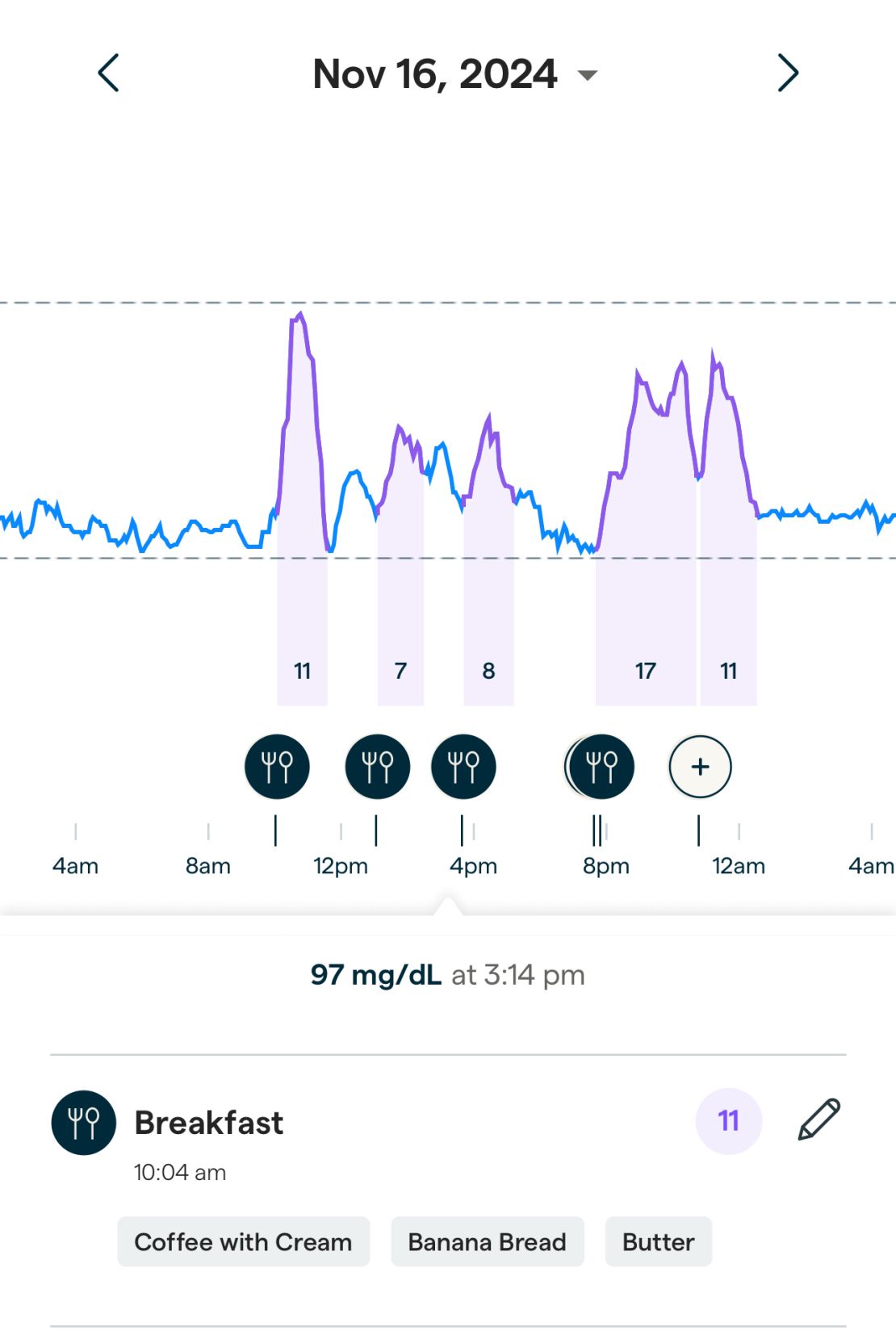

For the first week I wore the monitor, glued to the app, and was watching my glucose levels rise shortly after eating. The application stores that parameters It is called Lingo counts To help users understand the data, higher numbers are associated with larger or longer glucose spikes.

Even though the app gave me an initial target of 60 or less for a daily lingo count, I found myself trying to keep it as low as possible, a behavior reinforced by the app's recommendations to “balance” to do 20 squats after lunch. My count was increasing. At first I set my number very low and set my app daily target to 22, which I repeatedly exceeded once I lost some of my anxiety.

And while the finding that cheese doesn't lead to glucose spikes isn't all that surprising, there are a few other interesting readings.

Chopped veggies and quinoa, which I thought was a healthy choice for a quick lunch, scored the biggest lingo count of the week, probably because of the sugar in the peanut dressing. On the other hand, a glass of wine and a slice of pizza didn't cause a spike in blood glucose—not that a happy ending would lead to better health.

“Your values are completely normal,” Dushai said when I sent her the screenshots of my glucose levels. “What appear to be 'spikes' are perfectly fine visits within the normal range.”

But can those increases, even within the normal range, suggest ways I can feel healthier? Stay longer? Do you have more energy? Does it reduce my risk of developing metabolic disease? Or am I just learning that my “pancreas works as it should” as Marston puts it?

It depends on what you ask; The scientific community appears to be divided on the value of continuous glucose monitoring for people without diabetes.

“There are certainly a lot of strong opinions in the sector,” he said. Dr. Nicole Spartanoassistant professor at Boston University's Chobanian and Avedisian School of Medicine, studies the use of CGM in non-diabetics.

Spartano said she surveyed clinicians experienced in CGMS and asked them to interpret nearly 20 reports on glucose levels in people without diabetes.

“There's no consensus on how to look at the data,” she said. “Some people think high spikes are bad; some people think they're meaningless in people who don't have diabetes; some people think 'if the glucose cycle is too long,' people over 180 or higher should be screened for diabetes.” Other experts see that. They say that person is fine.”

Dr. Robert LustigProfessor Emeritus of Pediatrics at the Department of Endocrinology at the University of California, San Francisco, warns against excessive sugar and processed foods, saying it is important to reduce glucose levels in camp. Continuous glucose monitoring is useful for people without diabetes – if users have the right help to interpret their data.

“Not everyone will accept the same foods as everyone else,” says Lustig, the company's consultant. Levels Provides continuous glucose monitoring with one app. The goal is to lower your glucose, because when you lower your glucose, you lower your insulin, and when you lower your insulin, it's not to make the insulin go into fat, and that's not the cause. Cell proliferation at the heart of chronic metabolic disease.

Lustig acknowledges that people who use CGMs may experience the same anxiety I first felt about glucose data — but argues that anxiety can be reduced if users have more help interpreting the data. And Dushay and Spartano emphasize that it's especially important for people with a history of disordered eating or other eating disorders to talk to their health care providers before using CGM.

But for some, the tools offer surprising insights into how different people react to food — as 's chief medical correspondent, Dr. Sanjay GuptaHe wore a CGM with his wife, Rebecca. Neither of them have diabetes, but they were curious about what they could learn to improve their health.

“When I eat blueberries, my glucose doesn't rise at all,” he said. “When you eat blueberries, glucose rises immediately.”

With rice, it is the opposite, the glucose level increases, but Rebecca does not. Indian flat bread, which has been eaten since childhood, has also seen a significant increase. And sometimes, Gupta, his glucose can reach up to 180 mg per DC liter. With a history of diabetes in his family, he discussed itChasing life” podcast, is enough to make him want to ditch those foods.

After wearing the CGM for four weeks – each biosensor device lasts for two weeks – I decided to take a break and make a better plan before applying my third and final monitor. I realized that the way I first approached it was, as Dushay says, an “artificial experiment”: I wasn't using CGM to get feedback on how I normally eat. I was eating abnormally in response to the CGM.

“The first biosensor [should be] To see what you're doing over time,…