Waukeshahealthinsurance.com-

Waukeshahealthinsurance.com-

Orange, Va.

A.P

–

Painted in large letters on the walls of the maternity ward is the motto, “Saving babies, one mother at a time.”

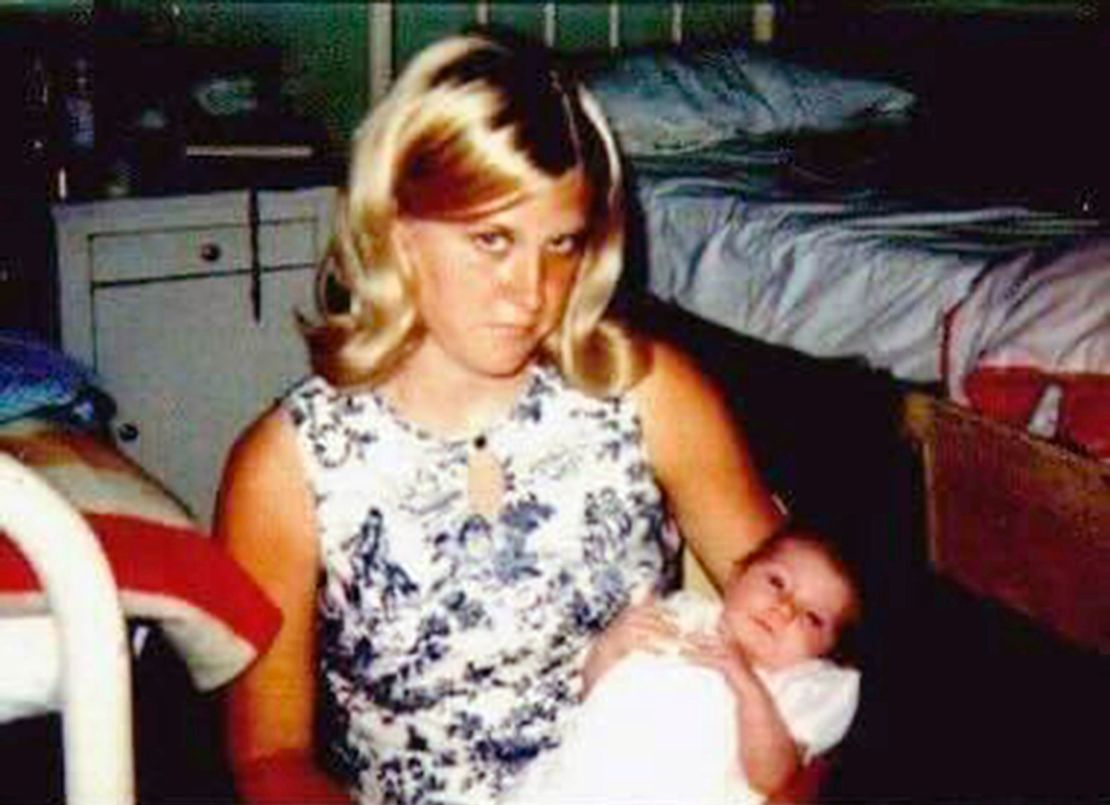

For founders Randy and Evelyn James, the house started with a baby – their own.

Paul Stefan was the last of their six children, born fatally. Doctors chose not to terminate the pregnancy. He lived just over 40 minutes to be baptized and named by a Catholic priest.

In the two decades since, James has channeled his son's memory and his anti-abortion beliefs into the maternity ward. “We knew we were going to do something for women in crisis pregnancy,” says Evelyn James.

In August, their Paul Stefan Foundation plans to open a new floor with seven additional rooms at their grand former hotel headquarters in Orange, Virginia.

Their momentum is part of a larger trend: In the two years since the Supreme Court struck down Roe v. Wade and the federal right to abortion, there has been a nationwide expansion of maternity homes.

After the court's decision, it rose 23 percent, said Valerie Harkins, director of the nonprofit Abortion Network 195, a “significant increase.”

According to Harkins, there are currently more than 450 maternity homes in the US; Many of them are based on faith. As abortion restrictions continue to increase, anti-abortion advocates want to open these transitional housing facilities, which often have long waits. It's part of the next step in preventing abortion and providing long-term support for low-income pregnant women and mothers.

“It helps the women say yes to carrying this pregnancy to term,” Harkins said. “Either they chose yes or maybe they felt they didn't have a choice.”

The reasons for the increased demand in maternity homes are complex and go beyond narrowing access to abortion. Inflationary paychecks and high birth rates in some states all contributed, Harkins said.

“It created a perfect storm,” she said. “There is a great need.”

The peak of American maternity homes comes from Roe v. Wade has been in the past three decades. During the so-called “Baby Scape Era,” more than 1.5 million babies were given up for adoption. Many unmarried pregnant women and girls were sent to live in maternity homes, often forced to abandon their children.

“Our children have been stolen from,” said Karen Wilson-Buterbaugh. In 1966, she was 17 when her parents sent her to Washington, D.C., to a home run by Florence Crittenton, a large chain of mothers started by progressive-era Episcopal reformers.

Back then, maternity homes were secret places to hide pregnancies. Residents often use aliases. Some even wear fake wedding rings in public. They had to pretend that nothing had happened when they returned to their hometowns without having children.

But few can forget.

Ann Fessler, who collected oral histories from mothers of the BabyScoop era, said in her book, “From the Gone Girls,” that she is “a mother who lost her child.”

Fessler, herself an adoptee, said, “The women, especially those who don't seem to have a stake in the decision, will live with this trauma for the rest of their lives.”

Harkins said the Maternity Home Coalition takes ownership of this story. He often discusses with members and at conferences.

“He's very dear to our hearts,” Harkins said. We are very deliberate about what happened and want to make sure we don't get to that point again.

The number of domestic infant adoptions has declined significantly since the 1970s. According to a 2016 analysis by researchers at the University of California, San Francisco, when women in one study were denied an abortion, they overwhelmingly chose parenthood (91%) over adoption (9%).

As the stigma against single parenthood diminishes, the majority of residents in modern maternity homes choose to keep their children. While the residents of the maternity home were once mostly middle-class, now poverty is the cause: mothers are there to find housing and financial support during and after pregnancy, sometimes for years after giving birth.

Currently, there are maternity homes that specifically focus on keeping children out of the foster care system. Others have increased their knowledge in addiction recovery. And while many help with adoption, some continue to prioritize and have relationships with adoption agencies – which can still lead to tragic outcomes.

Abby Johnson She was 17 and pregnant when her parents sent her to Liberty Godparent Home in 2008, the late Jerry Falwell, evangelical founder of Moral Majority and Liberty University. A Lynchburg, Virginia, maternity home contacted a nearby adoption agency.

Homeschooled and raised in a conservative Christian family, Johnson felt her unplanned pregnancy was treated as “the ultimate sin,” but she still wanted to raise her child.

“But they all told me this is not playing at home. He is not a doll. They deserve a couple who spend their lives together,” she said.

In a statement, the home said each resident is educated on parenting and adoption and has “freedom to choose.”

Eventually, Johnson was pressured to put her son up for adoption. Thinking that one day her son will know how much she misses him, she posts “silent mother” under the handle of social media.

“Half of my head lives in my mother's house,” she said, “and I'm replaying the memory over and over again.”

Before entering the maternity ward, Miriam had considered having an abortion.

New to the United States from Morocco, Bakache spoke little English and lived in a tight-knit family in northern Virginia, where her husband attended college in West Virginia.

“Where can I live with this baby?” she remembered thinking. “What can I give him? I don't have any.

Without health insurance, she sought medical care and found an anti-abortion counseling center — often called a crisis pregnancy center — that offered her an ultrasound.

“When I saw my son, everything changed,” she said.

The center's staff encouraged her to keep the child and find housing. Through a friend, she found Mary's shelter in Fredericksburg, an hour east of Paul Stephens' home.

Many birth centers accept referrals from similar centers to prevent women from having abortions. A member of the Paul Stephan and Mary Shelter, a coalition of maternity shelters, the Heartbeat International Project is one of the largest anti-abortion counseling centers in the country.

The fact that maternity homes are now associated with the anti-abortion movement is one indication—and one reason why critics say maternity homes are characterized by coercive behavior.

“I support housing and supportive housing for many people. Andrea Swartzendruber, a reproductive health researcher at the University of Georgia who studies anti-abortion counseling centers, doesn't think it affects a person's decision to have a baby.

Holding her infant son this summer, Bakach expressed her relief at seeing the beauty of the blue house she was assigned to stay at Mary's Shelter. And she was looking forward to the day she could work somewhere else with her husband and daughter.

Her housemate Jasmine Herriot was also looking for a safe place to live before giving birth to her second child. A certified nursing assistant, she lost her job and home after a life-threatening first pregnancy and premature birth.

“Everything was very clean. The room is all set. It was really a breath of fresh air,” said Herriot, with her newborn sleeping in her arms and her toddler playing by her side.

In the absence of a strong social safety net, maternity homes are filling voids in services for women and children. While residents may benefit from public assistance, neither Mary's Shelter nor Paul Stephan receive state or federal funds for their general operations. Other homes take public money: There are federal subsidies and at least five states have directed taxpayer dollars to maternity homes.

Maternity homes are springing up or expanding across the country. An old college campus in Nebraska is becoming a maternity home. He added a home to one property and opened another in Arizona. Lawmakers in Georgia recently made it easier to open new maternity homes with fewer state regulations.

Mary's Shelter has recently expanded by opening another home. Like James, founder Kathleen Wilson, inspired by her Catholic and anti-abortion beliefs, grew over 18 years to start the service, which now includes more than 30 bedrooms in six houses and four apartments.

They welcome women with many children, and despite their faith-based roots, have no religious requirements for residency. Residents sign a “healthy living” pledge, though Wilson won't try to evict anyone.

She found that the anti-abortion movement often advocated only for unborn babies and little care for families after birth.

Wilson thinks maternity homes are one answer to the criticism that “they challenge the lie that we only care about the baby in the womb.”

By Paul Stephan, churches and civic groups decorate each bedroom, some of which are decorated in blue and shades of blue. Illustrations line a sunny yellow corridor, with painted giraffes lining one side.

Upstairs, Danielle Nicholson says she lived at Paul Stephan's for about five years, when the back-dwellers spread out among the different houses. Now she is one of his success stories, recently raising a sixth grader.

But she arrived at the age of 20, six months pregnant and feeling abandoned. “You don't end up in a maternity ward because you have a big, huge, loving family village,” she says.

Evelyn and Randy James remain as parents to her. “Women are not numbers here. Or case files,” she said.

…